In Brief

Institutions can’t cut, grow, or spend their way out

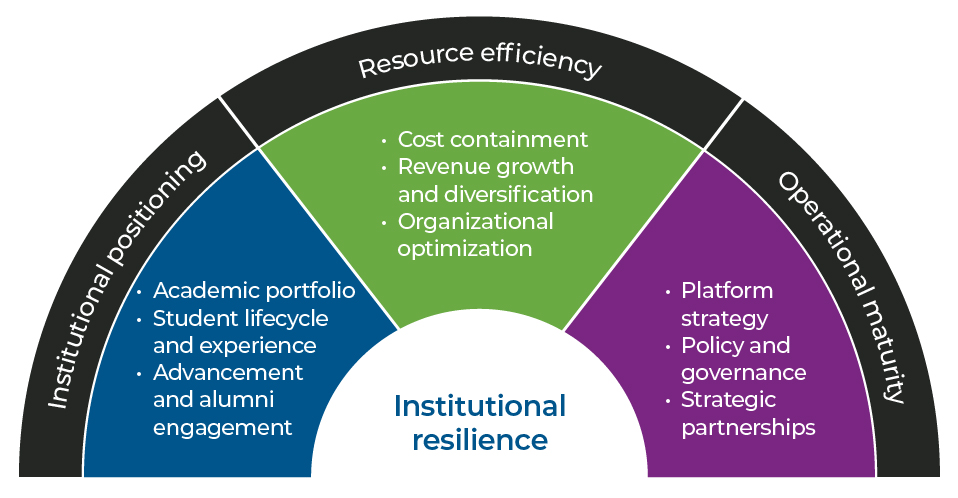

- Higher education faces major disruption, with financial impacts threatening many institutions' ability to operate. Achieving resilience isn't about cutting costs or growing revenue alone, but a balanced mix of revenue generation, cost reduction, and budget reallocation.

- To address these complex issues, leading institutions will define the right problem, not just the immediate one — which involves comprehensive financial forecasting and engaging with the community to identify areas of opportunity.

- Understanding and making trade-offs is critical. Institutions need to decide on a portfolio of initiatives that closes the financial gap and invests in a long-term strategy, as inaction is far riskier than an incomplete strategy that is being pursued.

Higher education is undergoing a period of significant disruption, and many institutions face financial impacts that threaten their ability to operate. For some institutions, this is a new challenge, driven by the recent changes in legislation that fundamentally alter their long-standing cost and revenue assumptions. For others, this is just another straw on the camel’s back that exacerbates already strained financial situations. The immediacy and severity of the problem seem to draw the same conclusions of “we have to cut everywhere” or “every department has to find X% in their budgets.” However, the reality is that you can’t cut your way out, grow your way out, or even spend your way out. Achieving institutional resilience is not driven by any singular change but by building a well-balanced portfolio of initiatives that can be integrated into multiyear budget planning.

Reductions in direct expenses, whether labor or non-labor, are the most actionable changes that can be made. But jumping to that conclusion too soon can obscure the reality that higher education is built on intersections. Reducing student support staffing may save dollars today, but a 0.5% decrease in first-year retention may more than offset any gains in years to come. Reducing the department budget may help bend the cost curve but can impede the ability to recruit top faculty talent. These are only hypotheticals, but they highlight an essential message for institutions. Yes, cost reduction is a significant part of the strategy. Still, the truth is that institutions cannot achieve resilience if they solve today’s problems by handicapping their ability to solve tomorrow’s — and that requires a well-informed mix of revenue generation, cost reduction, and budget reallocation.

Define the problem

The first step in developing an actionable plan towards resilience is to define the problem. Institutions must go beyond just projecting the impact of a single change and instead comprise a comprehensive financial forecasting effort that projects all key revenue drivers (e.g., enrollment, pricing, financial aid, auxiliaries, advancement, and giving) and all key expense drivers (e.g., compensation, benefits, non-labor spend, and debt service). It is common for institutions to solve for next year’s deficit when a rigorous financial analysis shows that the full extent of the problem won’t hit until several years down the road. These two problems often have very different solutions, and approaching them with just a 12-month mindset may severely limit the ability to adapt to those future challenges. Building resilience is only possible when you define the problem — and make sure you’re solving the right one in the first place.

Defining the problem also helps institutions communicate with the community. Engaging with faculty, staff, and other governance groups about why the institution must make these hard decisions is essential. There has been success at institutions that have been direct, clear, and intentional in their messaging to the community, and similarly, there have been some failed changes when organizations deprioritize communication and the community does not believe in the plan. No person can drive change alone in higher education, and it’s just as important to explain the problem in human terms as it is to define it on a balance sheet.

Expand the portfolio of solutions

Colleges and universities don’t pursue cost reduction out of a desire to ‘cut.’ Instead, institutions often look to cost reduction opportunities simply because they are the most easily understood and influenced variables. Again, cost reduction will have a role to play here, but the most effective next step toward resilience is to expand the number of possible solutions. And that must include a focus on revenue generation, new investment, and resource reallocation.

The nine drivers of institutional resilience can help with the exploration process, ensuring the assessment is truly comprehensive and cross-functional. Many critical areas are overlooked because of a premature belief that they don’t have something to offer. For example, areas like non-tuition revenue are often heavily underutilized in margin improvement initiatives because there is the perception that they don’t move the overall needle enough (e.g., increasing summer housing costs by $50 doesn’t solve the $50M deficit). However, if a single opportunity realizes $100,000 in new revenue, it can offset the need to eliminate a position, making the institution that much stronger in the long run. It takes time and commitment to identify the full set of options, but this effort unquestionably provides a return on investment and puts the organization on a more realistic path to stability.

Understand the trade-offs (and then make them)

The final portfolio of initiatives should represent a strategically aligned set of actions that best support the institution in closing the gap. And that is only possible by being realistic about trade-offs. Deciding whether to proceed with any given action comes with a benefit and a cost. An institution may opt to reduce discount rates for upcoming classes, which may hinder its ability to recruit in certain populations but minimize the need for workforce reduction. An institution may invest in student support efforts to drive up retention/net tuition revenue but may need to reallocate funding from an expected expansion in athletics. Colleges and universities can’t do everything, particularly in a challenging landscape, and building resilience requires institutions to quantify the trade-offs diligently and have difficult conversations about which path best aligns with a long-term strategy.

The most important step in this process is making the decision. Efforts to build resilience don’t halt due to a lack of options but rather from the hesitancy to select from those options. Higher education is mission-driven, student-centric, and a community dedicated to supporting social mobility. That same mindset makes it very challenging to decide whether to reallocate resources or deprioritize a specific area. However, the cost of inaction is exponentially more damaging than committing to an informed, strategic, but ultimately imperfect approach. The work will be difficult, and the landscape is changing more than ever, but every institution can build a path toward resilience that positions them for short- and long-term success.